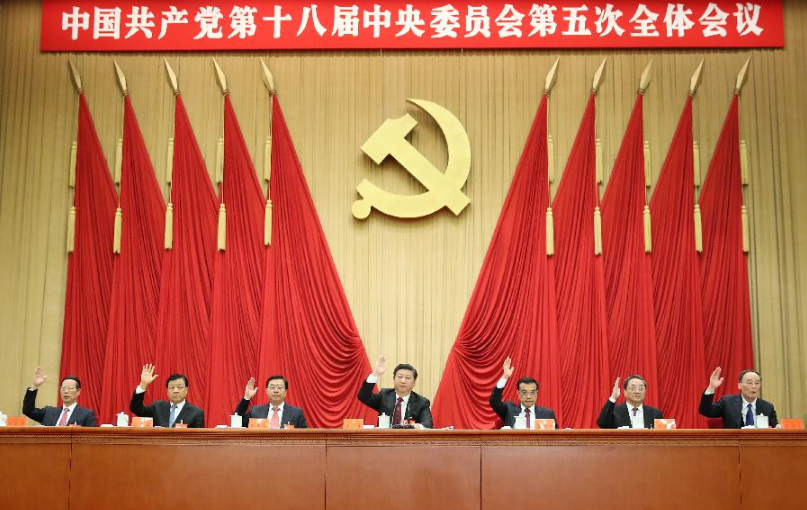

New York Times reported on July 16 that President Trump is considering widening the visa ban on Chinese Communist Party (CCP) members.

Currently, Party members are barred from becoming permanent residents (green card holders) and citizens, with some exceptions.

Paul Mozur and Edward Wong report for the Times that the proclamation could:

- Bar CCP members from receiving nonimmigrant visas;

- Extend to family members;

- Authorize the State Department to revoke the visas of CCP members presently in the U.S.;

- cover certain People’s Liberation Army members and executives at state-owned enterprises; and/or

- Target only the 25 members of the ruling Politburo and their families.

The Times argues that trying to identify Party members could be difficult. But the reporting omits mentioning that the Departments of State and Homeland Security have decades of experience hunting for Communists to enforce laws that have barred them from coming to the U.S. temporarily, as immigrants, and as naturalized citizens. Bureaucrats no longer seem to relish the hunt. Despite broad powers, in fiscal year 2017, only 15 applicants for immigrant visas worldwide were found ineligible on this basis, according to State Department statistics. That year, 35,350 persons born in Mainland China were issued immigrant visas. In 2018 and 2019, the number of persons found ineligible actually dropped.

Historical Development of the Law

Communists have long been subject to exclusion and deportation from the United States.

A statute enacted in 1903 banned “anarchists, or persons who believe in or advocate the overthrow by force or violence of the Government of the United States or of all government or of all forms of law.”[

In 1940 Congress broadened the bar to include those “who, at any time, had advocated or were members of or affiliated with organizations that advocated violent overthrow of the United States Government

The Internal Security Act of 1950 was the first statute to explicitly make Communist Party membership a ground for inadmissibility. At that time the Cold War was heating up. The Soviet Union consolidated its influence over Eastern Europe. The CCP had gained control over mainland China in 1949, forcing the Nationalists to retreat to Taiwan. The Korean War broke out in 1950. Senator Pat McCarran (D-Nev.), head of the Judiciary Committee’s Internal Security Subcommittee, was the Act’s chief proponent. McCarran believed that internal treason in the State Department had resulted in the “fall” of China to the Communists, and he adamantly opposed any recognition of the People’s Republic of China.

The Internal Security Act’s stated purpose was to cope with espionage and violence associated with efforts to “establish a Communist totalitarian dictatorship” in the U.S. and throughout the world. The Act designated Communist Party membership as a basis not just for inadmissibility but also for deportation and denial of naturalization. Most controversially, the Act required American Communist Party members to register with the Attorney General and called for investigations into Communist-front organizations so they could be required to register as a precursor to placing them in detention camps in time of emergency. President Truman vetoed the bill, commenting that “The basic error of this bill is that it moves in the direction of suppressing opinion and belief…that would make a mockery of the Bill of Rights and of our claims to stand for freedom in the world.” Nevertheless, Congress overrode Truman’s veto, and the bill became law.

During the McCarthy era, the U.S. government vigorously enforced the ideological grounds for exclusion and deportation. Those grounds remained in place throughout the following decades. That period witnessed ups and downs in the U.S.-China relationship. The two countries faced off in Vietnam. Nixon’s 1972 trip to China led to a rapprochement.

Critics argued that the law was used to exclude persons with unpopular associations and beliefs who posed no danger to the public. In one such case, the Supreme Court found there were facially legitimate grounds for the State Department to deny a visa to a well-known Marxist theorist who was coming to lecture at various U.S. institutions, despite the claim of schools and professors that the visa denial restricted their free exchange of ideas protected by the First Amendment.

There is some merit to the argument that exclusion based on ideology harms U.S. citizens’ right to hear and associate with noncitizens. Banning an author is not so different than banning a book. And such bans harm U.S. citizens’ ability to associate with their overseas relatives. (President Trump’s own father-in-law, Victor Knavs, now a naturalized U.S. citizen, was reportedly a Communist Party member in his native Slovenia.)

Reflecting such criticisms, in 1987 Congress provided that no noncitizen could be excluded or deported because of past, current, or expected beliefs, statements, or associations that, if engaged in by a U.S. citizen in the United States, would be protected by the U.S. Constitution. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-N.Y.), speaking in favor of the bill, argued that the prior law was “an unnecessary, and most damaging, legacy of the McCarthy era… [B]y excluding aliens whose only threats to us were ideas, we exposed our Nation to needless ridicule and undermined the respect for free speech we hope to promote around the world.” This temporary law was allowed to expire three years later.

In 1989 Berlin Wall fell, followed by the collapse of the Soviet Union. Shortly thereafter, the Immigration Act of 1990 created the current statutory regime. It eliminated the ground of inadmissibility as it applied to nonimmigrants as well as the ground of deportation for Communist Party members. It left in place the ground for denial of naturalization, as well as the ground for inadmissibility as it applies to immigrants. The House Conference Report stated that admission to the U.S. “is not a sign of approval or agreement” with a noncitizen, so persons should not be “excluded merely because of the potential signal that might be sent because of their admission, but when there would be a clear negative foreign policy impact associated with their admission.”

The Current Ban on Permanent Residence

Generally speaking, “membership” in “the Communist or any other totalitarian party” makes a person may be ineligible for a green card. INA § 212(a)(3)(D)(i). See INA § 101(a)(37) (defining “totalitarian party”).

So does membership in any organization “affiliate[d]” with such a Party. INA § 212(a)(3)(D)(i). In China, such organizations include minor political parties and mass organizations (e.g., Communist Youth League, All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce, All-China Federation of Trade Unions, All-China Women’s Federation). Such organizations are led by the Party, which uses them to penetrate the society at large and encourage popular support for Party policies. Robert L. Worden, et al, China: A Country Study (GPO 1987), http://countrystudies.us/china/107.htm.

For example, the Communist Youth League (中国共产主义青年团) is an organization for youth between ages 14 and 28. The CYL is organized on the Party model. Its goal is to train youth to practice socialism and communism “with Chinese characteristics. Although CYL membership is not required for full Party membership, it does facilitate the path. CYL has over 70 million members. Almost all high school graduates are CYL members.

Further, a person who is not a member of the Party or any other proscribed organization ineligible for a green card if he or she has been “affiliated with” the Party or one of these other organizations. Id. “Voluntary service” in a “political capacity” does constitute “affiliation with” the Party. 22 C.F.R. § 40.34(c). And “employment in a responsible position in the government,” including the military, of a communist-controlled country” is presumed to be “voluntary service.” 9 FAM 302.5-6(B)(4). A “rank-and-file” government workers doesn’t count as a person in a “responsible position.” Id.

Distinguishing whether a particular applicant is in a “responsible” or “rank-and-file” position may not always be easy, but it likely turns on the applicant’s position in the government hierarchy and the extent of their political responsibilities as opposed to professional responsibilities. For example, “continuing service and/or promotion to a higher rank, e.g., the officer corps, could result in the alien’s serving in a political capacity.” Id.

Possession of a diplomatic, special, or service passport issued by a communist country may be an indication of “affiliation.” with a proscribed organization.

But there are three important exceptions to ineligibility.

First, a person is admissible if the membership or affiliation terminated at least five years before the date of application. INA § 212(a)(3)(D)(iii) (or 2 years in the case of a country where the Communist Party doesn’t control the government). At least in theory, a member is free to withdraw. CCP Const., art. 9. Also, inactivity can lead to termination of membership. A Party member who fails to take part in regular Party activities, pay membership dues or do work assigned by the Party for six successive months without good reason may be regarded as having given up membership. Id.

Second, a person is admissible if membership or affiliation is involuntary, including but not limited to “solely when the alien is under 16 years of age” or where necessary for purposes of obtaining employment, food rations, or other essentials of living. INA § 212(a)(3)(D)(ii). In China, it may be difficult to prove that CCP membership is “necessary” to obtain the essentials of life because alternatives to CCP membership are clearly better today than they were in the 1970s. In particular, private entrepreneurship has become an increasingly viable alternative to party membership. In China, many non-CCP members succeed in business, have security of person, benefit from the country’s economic growth, and so on.

Third, a person is admissible if his or her association with the Party is “not meaningful,” meaning that he or she lacks “commitment to the political and ideological convictions of communism.” 9 FAM 302.5-6(B)(6). This is a judicially-created rule, and it is difficult to neatly synthesize the cases. The leading case, Rowoldt v. Perfetto, was about a man who for about a year paid dues to the U.S. Communist Party, attended meetings, petitioned the government related to unemployment laws and the government budget, worked at a Party bookstore, and stated that his purpose in joining the party was to get jobs, food, clothes, and shelter for the people. 355 U.S. 115 (1957). He denied opposing democratic principles. He denied any commitment to violence and denied that violence was discussed at any meetings he attended. His Party membership ended only when he was arrested and charged with being deportable due to his membership. The Supreme Court held that he qualified for the non-meaningful association exception because his understanding of party’s principles as “unilluminating” and the “dominating impulse” of his affiliation with the party was “wholly devoid” of any “political implications.”

Today, CCP membership isn’t necessarily ideologically meaningful. Since the 1980s, when reform policies brought great improvements to China’s standard of living, traditional Communist ideology has been overturned by contrary slogans such as “To get rich is glorious,” a saying attributed to former paramount leader Deng Xiaoping. The CCP continues to pay lip service to Marxist-Leninist ideology, but ideology has become a post hoc rationalization device. Deng also said, “It doesn’t matter if a cat is black or white so long as it catches the mouse.”

Instead, Party membership is often sought because the CCP is “a sort of Rotary Club of 70 million people who joined in because it’s good for their careers.” See David L. Shambaugh, China’s Communist Party: Atrophy and Adaptation 25 (2008), quoting Harvard Professor Rod MacFarquhar. The Party is a mutually advantageous social network that distributes favors and privileges (guanxi) to its members. Mere membership in the party also signals elite status to potential government or private employers. It’s “shorthand for being an excellent person.” See Jamil Anderlini, et al., Welcome to the Party!, FT Magazine (Sept. 28, 2012). Membership is also a hedge against political risk, not unlike emigration. So it’s not uncommon for a person to write up a party membership application with one hand and fill in a U.S. immigration application with the other.

Finally, in addition to these exceptions to ineligibility, there is also a waiver available in the case of the parent, spouse, son, daughter, brother, or sister of a U.S. citizen; or the spouse, son, or daughter of a lawful permanent resident. The applicant must be seeking admission for humanitarian purposes, to assure family unity, or for other reasons serving the public interest. The applicant must not be a threat to U.S. security and must merit a positive discretionary finding. INA § 212(a)(3)(D)(iv).

Procedurally speaking, the government asks about communist party membership in the immigrant visa application form (DS-260) and the adjustment application form (I-485). The applicant and counsel should be prepared for related questions during the interview and should document eligibility for a waiver or the applicability of an exception to the ground of inadmissibility. A legal brief may be helpful.

Immigrant visa applicants also need to be prepared for possible delays while the consular officer seeks a security advisory opinion from the Department of State in Washington, DC. See former 9 FAM 40.34 N3.3-1, N4.3, N4.4.

Current Ineligibility for Citizenship

To apply for naturalization, an applicant must prove he or she is loyal to the principles of the U.S. Constitution and the basic form of government of the United States. INA § 316(a); 8 C.F.R. § 316.11(a).

A person is ineligible for naturalization if he or she

- has been a member or affiliate of the communist party or of any affiliate of the party;

- advocates the doctrines of world communism or the establishment of a totalitarian dictatorship in the United States; or

- writes, publishes, or circulates printed matter advocating the doctrine of world communism of the establishment of a totalitarian dictatorship in the United States.

There are exceptions for persons whose membership terminated more than 10 years before applying for naturalization and for involuntary membership or affiliation. INA § 313(c), (d). There is also an exception for non-meaningful membership or association. See Legacy INS Interpretations 313.2(c).

Conclusion

The details of Trump’s draft presidential proclamation are still opaque. But I’m not in favor of broadening already bad law, especially since the motivations for the a proclamation appear to include xenophobia and a desire to whip of the President’s base prior to the election.

I agree with former Senator Moynihan that this law is “an unnecessary, and most damaging, legacy of the McCarthy era.” Expansion of the ideological ban would further “expose[ ] our Nation to needless ridicule and undermine[ ] the respect for free speech we hope to promote around the world.”

Leave a Reply