An immigrant visa applicant sporting a tattoo may be questioned about it. The presence of tattoos is noted during the required medical exam. This may lead a consular officer to suspect the applicant has gang affiliations or has abused drugs.

Some applicants say their visas have been improperly denied on the basis that they are “gang associates” who intend to enter the United States to engage in unlawful conduct. [a] Other applicants say their cases have been referred to the Visa Office, taking months or even years to clear. [b] The State Department’s position is that a tattoo may be one piece of evidence as to whether an applicant is a security risk but that refusals for security reasons are based on the totality of evidence, including the applicant’s law enforcement and immigration records. [c]

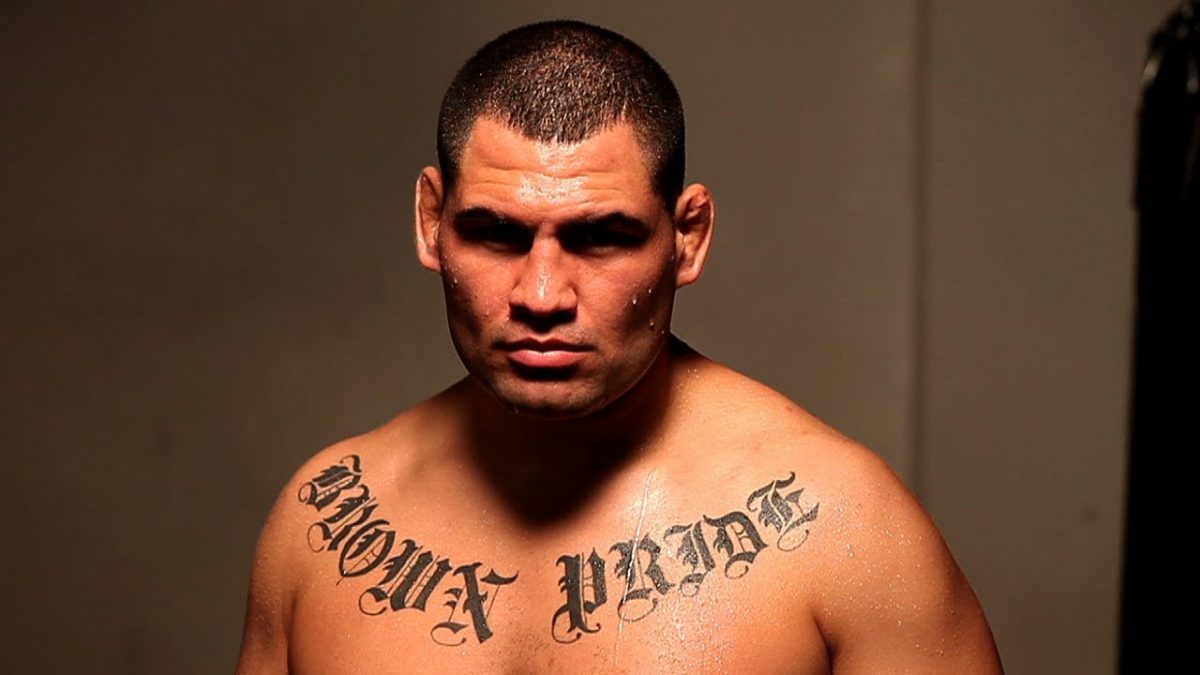

It can be difficult to discern whether tattoos are gang identifiers. For example, Rolando Mora-Huerta was denied a visa based on evidence that he had once been stopped by police in a car driven by a man with a “Brown Pride” tattoo. The police suspected the driver of ties to the Sureno gang, who were known to have similar tattoos. Mora was unsuccessful in arguing that the tattoo merely symbolizes pride in Latino heritage. [d]

Law enforcement agencies catalog gang tattoos. One example is the Canada Border Services Agency’s Tattoos and Their Meanings (2008).

One type of record that the State Department may rely on is a gang database kept by a U.S. law enforcement agency. Such databases help police analyze trends and prosecute cases. But activists claim these databases may include inaccurate information. For example, Luis Pedrote-Salinas claims he was arrested in Chicago in 2011 for having an unopened Bud Light beer can. The police wrote in the Chicago gang database that he admitted to being a member of the Latin Kings, which he denies. Although the criminal case was not prosecuted, the listing in the database prevented Pedrote-Salinas from qualifying for relief under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. He is suing the Chicago Police Department, arguing that there should be an official process to get off the database. [e]

In another scenario, some applicants say that consular officers have, upon seeing tattoos (for example, a tattoo of a marijuana leaf), referred them for psychological interviews to investigate drug abuse. In some cases, following such exams, visas have been denied, even for one-time marijuana use. [f]

Immigration lawyers may work with clients to document that tattoos are not gang- or drug-related, or to document that any gang affiliation or drug abuse has ended, and to prepare clients for related questions during the medical exam and consular interview.

Removing a tattoo or covering it with another tattoo may not be a successful strategy, as the doctors performing medical examinations have been known to discern the original tattoo with UV light.

Has your appreciation for body art impacted your visa application? Let us know in the comment section.

—

[a] AILA-U.S. Consulate in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, Liaison Meeting Minutes, Dec. 10, 2013; AILA-U.S. Consulate in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, Liaison Meeting Minutes, Apr. 27, 2012. The statute, INA 212(a)(3)(A)(ii), allows visa refusals if an officer has “reasonable grounds to believe” the applicant seeks to enter the U.S. to engage in unlawful activity. Such refusals require concurrence from the State Department.

[b] Davis, Tonello, et al., Update on the U.S. Consulate General in Ciudad Juarez, Dec. 2012.

[c] AILA-U.S. Consulate in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, Liaison Meeting Minutes, Aug. 21, 2012.

[d] Cardenas v. United States, 826 F.3d 1164 (9th Cir. 2016).

[e] Odette Yousef, Activists: Gang Database Disproportionately Targets Young Men of Color, NPR (Jan. 27, 2018).

[f] Davis, Tonello, et al., Update on the U.S. Consulate General in Ciudad Juarez, Dec. 2012.

Leave a Reply