On August 2, White House adviser Stephen Miller held a press conference defending President Donald Trump’s support for the RAISE Act, legislation that would reduce legal immigration to the United States.

CNN reporter Jim Acosta asked whether the bill is in keeping with Emma Lazarus’ sonnet, The New Colossus, at the base of the Statue of Liberty, which reads in part:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me.

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

Miller dismissed Acosta’s idea:

The Statue of Liberty is a symbol of liberty enlightening the world…. The poem that you’re referring to was added later. It’s not actually part of the original Statue of Liberty.

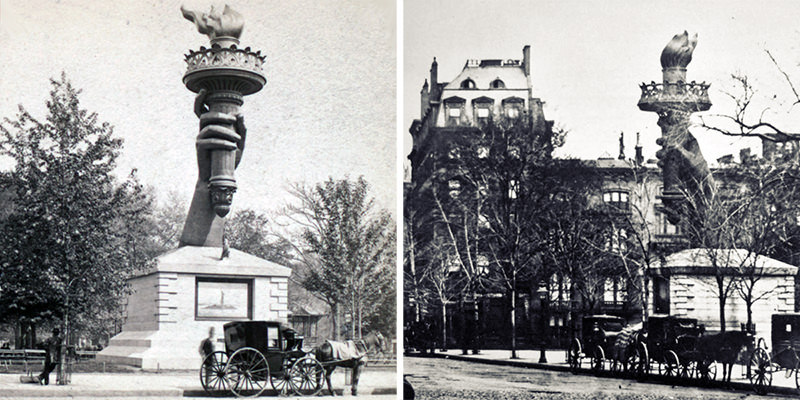

The statute portrays Libertas, the Roman goddess of freedom, holding a torch above her head and, in her left arm, a tablet inscribed in Roman numerals July 4, 1776, the date of the Declaration of Independence. A broken chain lies at her feet.

Technically, Miller is correct that the plaque with Lazarus’ poem was added later. But what of Miller’s implication that the Statue of Liberty is not a symbol welcoming immigrants?

Edouard Rene de Laboulaye first proposed the idea for the Statue of Liberty. He was a French statesman, law professor, antislavery activist, and an advocate of the Union’s cause during the Civil War. When he announced the project, he named the statue, Liberty Enlightening the World. Laboulaye saw Liberty as a universal ideal, and considered American Independence (won with French support) and abolition of slavery as important steps towards that ideal.

The statue’s 1886 dedication ceremony did not mention refugees. Still, the Declaration of Independence, portrayed in the statue, does bring to mind one of the grievances listed by the colonists against King George III:

He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners ; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.

Yet that’s not exactly a call for protecting refugees. Instead, immigrants were welcomed because America was so huge, underdeveloped, and sparsely populated, and immigrants were needed to help develop it. Nonetheless, the Declaration’s referral to “unalienable Right” to “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” has since been read to have greater implications.

Emma Lazarus, an American poet, was moved by the plight of Jewish refugees who had fled pogroms in Tsarist Russia, and she helped establish the Hebrew Technical Institute in New York to provide them with vocational training. She wrote The New Colossus in 1883 after she was asked to donate an original work for a fundraising auction for the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal. Later, in 1903, a bronze plaque with the poem inscribed was added to the statute.

While the statue was under construction, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Its preamble claimed that “the coming of Chinese laborers to this country endangers the good order of certain localities.” The Act placed a ten-year moratorium on entry to the U.S. of Chinese laborers, required registration of all Chinese laborers already in the U.S., and denied them naturalization as U.S. citizens. This was the first U.S. law to ban immigration based on race or nationality. It focused on laborers but effectively reached all Chinese people except travelers, merchants, teachers, students, and those born in the U.S. The law was extended several times and was effective until 1943.

As background, the nineteenth century the U.S. witnessed two waves of Chinese immigration. The first came after the discovery of gold in California in 1848. The Chinese, like other immigrants, came hoping to strike it rich in the mines. The second wave began in the 1860s during the construction of the Central Pacific Railroad.

Migration was also influenced by poverty and instability at home. The Opium War with Britain (1839-42) spawned resentment towards foreigners, but the ensuing economic troubles also drove some to emigrate. Then the Taiping Rebellion (1850-64), led by the self-proclaimed Son of God, Hong Xiuquan, took twenty to thirty million lives and increased the flow of refugees.

During the early stages of the gold rush, when gold was plentiful, the Chinese were tolerated. But as gold became harder to find and competition increased, animosity toward the Chinese grew. Forced out of mining and other occupations, many Chinese settled in enclaves in cities like San Francisco and took up low-end work in restaurants and laundries. Nativists stoked anti-Chinese sentiments. This included labor leader Denis Kearney, leader of the Workingman’s Party, as well as by California Governor John Bigler, both of whom blamed Chinese “coolies” for depressed wage levels. Chinese immigrants even faced racial ostracism and violent assaults, including the 1887 Snake River Massacre in Oregon, at which 31 Chinese miners were killed.

Still, some Americans opposed the nativists. For example, Senator George Frisbie Hoar (Republican–Massachusetts), an anti-slavery activist, considered the Chinese Exclusion Act as the legalization of racial discrimination.

Saum Song Bo, pictured above with others from his Old University of Chicago medical school class, in 1884, was asked to contribute for construction of the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal. He wrote in response:

I feel that my countrymen and myself are honored in being thus appealed to as citizens in the cause of liberty…. That statue represents Liberty holding a torch which lights the passage of those of all nations who come Into this country. But are the Chinese allowed to come? As for the Chinese who are here, are they allowed to enjoy liberty as men of all other nationalities enjoy it? Are they allowed to go about everywhere free from the insults, abuse, assaults, wrongs and injuries from which men of other nationalities are free? …

Whether this statute against the Chinese or the statue to Liberty will be the more lasting monument to tell future ages of the liberty and greatness of this country, will be known only to future generations.

Liberty, we Chinese do love and adore thee; but let not those who deny thee to us, make of thee a graven image and invite us to bow down to it.

If Saum Song Bo and Steve Miller were to meet, they would agree that the Statue of Liberty was not originally intended to be a symbol welcoming immigrants to America. The difference is that Bo hoped that over time America perhaps would correct the injustice of the Chinese Exclusion Act, taking another step towards the goal of universal liberty symbolized by the statue. In contrast, Miller misinterprets the meaning of the statue because he fails to understand the universal message of liberty intended, not to mention the history of over 100 years associating the statute with Lazarus’ poem welcoming refugees.

(H/t to the Washington Post’s Constitutional Podcast, for introducing me to Bo. For more of the statue’s history, see John Bodnar, et al., The Changing Face of the Statue of Liberty).

Leave a Reply